Why Platform Orchestrators Are the Missing Link in Your Internal Developer Platform

- Daniel Bryant

- Jul 10, 2025

- 7 min read

For many years, my peers and I have been discussing the concept of building “golden paths” for developers. These golden paths lead the way to easing developer cognitive load and providing a semi-opinionated set of workflows and tools that enable them to code, ship, and run their applications more efficiently. At the same time, this improvement to the developer experience should enhance the organisation’s ability to derive greater value from its development teams and investments.

This, broadly speaking, is what platform engineering is all about. But what exactly is a platform, and what does or should it contain? What does it need to be and do to live up to its promise? While the phrasing and terminology may change incrementally over the years, I’d argue that the “missing middle” is one of the critical parts of a platform and is, in part, why many organisations struggle with adoption and use even after investing in building and deploying internal developer platforms.

Getting unstuck by placing a platform orchestrator in the middle of the mix could be just the approach many organisations need.

But first… what is a platform, anyway?

While no canonical definition of a developer platform exists, there is a tacit consensus around something like the following: A digital platform is a foundation for self-service APIs, tools, services, knowledge and support arranged to enable work at a higher pace with reduced coordination. Gartner has augmented this definition by adding to it an “improved developer experience and productivity via self-service capabilities and automated infrastructure operations”.

A shared understanding of what a platform is, however, is just the beginning of building a platform, and real-world implementations have often yielded mixed results. Serving as a signpost that platform engineering is close to reaching (or already in) the “trough of disillusionment” phase of the hype cycle, failed expectations for platform engineering aren’t all bad news. In fact, it’s in these troughs, deep with disappointment and pushback, that we can learn the most.

With platforms, we are starting to see how important users and their input and feedback are to building a fit-for-purpose platform… and a critical moment for moving towards filling in the missing middle. It’s here that we can discover the why behind resistance to platform adoption, the reasons a platform isn’t working for its users, and potentially remove some friction and some of the challenges and objections developers have lodged against earlier iterations of platforms.

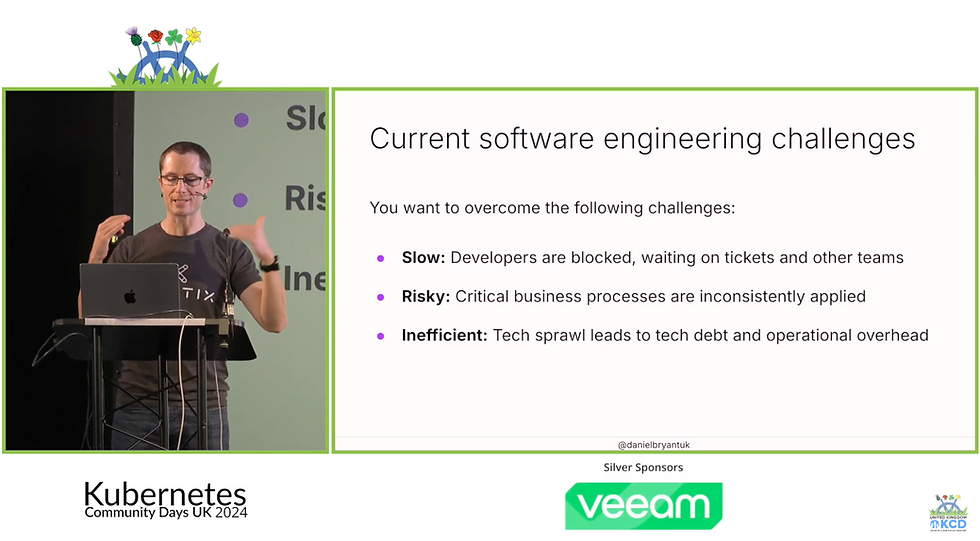

Why do we need platforms?

In an ideal world, organisations know they need developer platforms to overcome a handful of key challenges.

While they might cite any number of different problems, most of the critical ones come down to three things, which can be tied directly to the goals for a developer-friendly (and business-friendly) platform:

Speed: Developers are blocked. They need to move faster and increase productivity without negatively impacting developer experience.

The organisation needs a platform to provide “everything-as-a-service” to help rapidly and sustainably deliver value to end-users. “Everything” here depends on the business, but for example, one org might need to define a database-as-a-service that anyone in the org can access. In contrast, another organisation might have specific needs; for example, in financial services, there may be a requirement for Know Your Customer (KYC) as a service or fraud detection as a service.

Risk: Critical business processes are inconsistently applied, exposing potential risks and consuming a significant amount of time on repetitive tasks.

The org needs a platform to automate manual processes in reusable components. Many critical functions, such as sign-offs and security checks, must be performed repeatedly. Therefore, it’s better to do them once, learn from the process, codify the steps, and automate them for greater security and efficiency.

Inefficiency: Too much technical debt and operational overhead are creating major inefficiencies.

The org needs a platform to scale efficiently and to deploy resources as a fleet. This becomes possible once the speed and safety issues are addressed.

Understanding why a platform is needed is also a key element in understanding how it will be used by developers, which leads to designing and building for the developer audience and moving away from the trough of disillusionment.

Use is key: How to build a developer-friendly platform

Talking to the future users of a platform is the best, if not the only, way to find out what a platform needs to provide. This means understanding the workflows, tools, processes, and so on, that developers rely on every day. It means observing how they work in addition to talking to them about what would make their jobs easier and relieve some of the burden of running things or learning about things that feel more like roadblocks on the way to productivity.

And it’s only once you’ve done the real-user research that you can craft a plan for how to build a developer-friendly platform.

First of all, there is no one single right way to do it. It depends on the context of your business, what you need to achieve, and how developers already work.

And second of all, there is some acknowledgement that there’s a “middle-out” ground for platform development that is likely to get you where you want to go. If we look at different ways and hows of building platforms, we can easily identify the positives and negatives of each method.

Top-down, developer-focused portals

Going top-down, developer-focused via portals is a great way to get started and get onboarded, but things become much more challenging when working on Day Two experiences. My colleagues and I often refer to this as the “puppy for Christmas” vibe. Everything feels new and exciting at the beginning, but the portal ultimately proves to have significant limitations and is somewhat like a façade. Upgrades and maintenance become difficult (or are not thought of at all).

While this provides a great initial developer experience, especially if you never had anything in place before, it rarely works as a scalable solution for the long haul, and you can even end up with teams built around one specific technology trying to support upkeep rather than having more generalist teams that can support broader engineering concerns.

Bottom-up infrastructure and ops-focused platforms

Bottom-up, infrastructure and operations-focused platforms deliver a lot of great workflows and flexibility, with everything-as-code and a highly automatable approach. But the infrastructure abstractions tend to leak through to developers who don’t necessarily need the added headache of understanding CRDs, the ins and outs of Kubernetes, and all manner of other full lifecycle issues, and this can lead to a big maintenance gap and the possibility of different tiers of platforms operating in parallel within your organisation at the same time.

This happens when we see “islands” of great platform stuff popping up in some places, co-existing with a bunch of old stuff that will never move across, so you end up with a two-tiered platform system that doesn’t really serve anyone effectively.

Middle-out middle-ground platform engineering

So the Goldilocks-style, middle-out, platform-engineering-focused approach, building a platform as a product, thinking X-as-a-service, building specifically for user needs, is where we land. The “missing middle” isn’t just one technology or service - it could be a lot of things working together, orchestrating and composing different things, such as workflow management, together in higher-level abstractions.

Many examples exist here, such as CNOE (AWS), which provides a middle layer that orchestrates everything from CI/CD to workflows. Or Humanitec’s reference architecture, which includes a platform orchestrator in the diagram. Or Kratix, which provides a framework for platform engineers to build the middle layer of their platform.

The unstuck middle: Holding everything together

Illustrating what this three-layered platform could look like, I’ve split it into an application choreography layer at the top, an infrastructure orchestration layer at the bottom, and nestled in the happy middle ground is platform orchestration.

The application choreography layer is where all the things needed for the software development life cycle live: the UI, CLI, declarative config, your coding, shipping, and running of software.

At the infrastructure orchestration/composition layer, there’s the planning, building, and maintaining of the platform. This is where DevOps, operators, sysadmins, and platform engineers live, working with CRDs, Bash scripts, etc., using tech like Terraform, Crossplane, Ansible, and so on.

And finally, the missing middle is where it all comes together: the platform orchestration layer. This layer focuses on platform API and lifecycle, and it’s where “design, enable, and optimise” happen. It is a bit like the icing between layers of cake, holding everything together.

Where the missing middle joins all the layers: Platforms as products

No organisation sets out to build products for the market without understanding why they are building it, who they plan to sell to, who their users are, and so on. Why would you take a different (and blind) approach to building an internal platform? Internal platforms are also products, and should be treated as such. Taking this product-led approach, platforms are built intentionally and with clear goals and measurements defined.

Once again, what does the platform need to deliver, and how will you know if it is meeting those targets? And does the platform continue to serve its purpose over its entire lifespan? After all, what gets measured gets managed. Some key leading and lagging indicators to consider include platform adoption rates, onboarding time, and time to pull request. Meanwhile, app retention rates, incidents or near misses mitigated, and ROI/time saved can help determine whether the product is successful.

And when building a platform and running into various hurdles, it may be that these hurdles are cues for examining the “missing middle” layer. For example, if you are struggling with day two issues, such as challenges with upgrading services or security incidents you cannot easily fix, or developers are complaining about learning Terraform or Crossplane or other abstractions and different technologies, look to the middle—the platform orchestration layer—to find a solution for smoothing this out.

Comments